Understanding Neurotypicals: A Guide for Autistics – Part 2 (Why?)

I’m working on a new series to help autistic people better understand their neurotypical loved ones. This is the second in the series. (If you missed the first one, check it out here.)

I’m very grateful for the neurotypical people who are helping me put this together.

Today, we’ll be talking about the word “Why?” For autistic people, the word “why” is a request for more information. There is almost no other reason an autistic person would ask this question, nor would we think it could mean something other than its literal meaning.

Since this is a very common communication issue between neurotypes, I asked my NT volunteers how the word “why” affects them and why it may get such a strong and confusing reaction in the eyes of an autistic person talking to them.

Here are the answers I received when I asked each neurotypical person how they took the word “why”:

NT (Neurotypical) 1:

“I think it’s because they feel like the “why” of the situation is common knowledge or that you should at least be able to figure out why with the information you already have. It interrupts their thought process. They feel like they are several steps ahead in the order of operations and someone asking why becomes disorienting and they blame you. It slows them down and they have to actually turn autopilot off and think about the question. I think most of them don’t even understand the why. It’s like an offensive call out.”

NT 2:

“That’s a bit difficult without more context. I think ‘why’ on its own is innocuous. However, if you mean when a child keeps repeatedly asking why? In this context, because NTs feel they have answered the question in the first or even second ‘why’. They most likely have no further info on the subject, so they think the child is just being precocious or trying to annoy them or uncover they don’t actually know as much about the subject as they thought they did!.

It can also tie in with social hierarchy – if an NT feels they have some kind of status, and they make an announcement, they feel that the question ‘why’ is a challenge to their power, i.e they have spoken and that should be enough.

Also, I think ‘why’ on its own, as opposed to ‘why is the sky blue’ can feel quite aggressive, like when someone said ‘so what?’”

NT 3:

“I think it is experienced by most as a very direct and intrusive (potentially judgemental) question, no matter the context.”

The Tone of Voice Component When Asking Questions

Since my neurotypical volunteers seemed to have struggled a bit with answering this question (because, as another NT person whose answer I did not include here explained, NTs often don’t know “why” they do things, it’s just automatic), I want to put a few more of my thoughts into this piece for context.

When you say the words “tone of voice” to an autistic person, many of us experience a deeply traumatic response to it. We cannot hear our tone of voice, but many of us have been punished throughout our lives for this “offense” we don’t understand. So, if you have an autistic person who has what is perceived by neurotypical ears as a monotone, flat, or angry voice, and that voice is coupled with the word “why”, it can sound challenging when that’s not the intention of the autistic person at all.

Now, add social hierarchy to this confusing interaction, and you’ve got a recipe for disaster.

I’ll give you a fictional example:

Holly is a 23-year-old autistic woman working as a secretary at a doctor’s office. Her job is to answer phones, schedule appointments, and file paperwork. She purposefully masks by smiling and forcing tone into her voice when she interacts with patients. Beyond that, she just allows herself to be herself. The doctor she works for is aware she is autistic, and that she occasionally stims on the job and needs to take regular breaks to decompress. He doesn’t mind.

However, one day he asks Holly to do something she hasn’t done before: Go out and pick up his dry cleaning. This doesn’t make any sense to Holly. She’s never done personal errands for her boss before, and she gets lost very easily when driving. She doesn’t know exactly where the dry cleaning place is or what it looks like, as it’s clear across town. GPS will help, but this is completely outside her routine and very strange to her.

She asks “why” with a flat tone and a blank facial expression. She doesn’t understand (and she is beginning to disassociate at even the thought of doing the task), which is one of the reasons she is coming across as flat and monotone. The doctor, who thinks he’s showing his trust in her by giving her more responsibilities, is offended by her question. He thinks she just doesn’t want to do it, or she views the request as sexist. Plus, even though he understands her (or thinks he does), he IS her boss, and he doesn’t think she should be questioning him as though she’s somehow on his level.

The doctor shows he’s offended by snapping at her, Holly gets confused and becomes panicked, and she’s sent home to take the rest of the day off. The doctor is annoyed and feels less trusting of Holly, and Holly is afraid he will ask her to do more things out of the scope of her position, and she will eventually end up being fired. It’s certainly happened to her enough times before.

What Holly was trying to convey was, “Why do you want me to do this? You’ve never asked me to before. It’s not in my job description. Also, I get lost easily, I don’t think I’ll be able to do what you’re asking. I’m incredibly anxious and afraid I’ll lose my job if I don’t do this, but I can’t do it.”

She wasn’t being insubordinate or questioning authority, she genuinely didn’t understand why her routine was being changed so drastically when she thought her boss understood her. Now, trust has been broken for both parties because of this misunderstanding, and the relationship and work environment will inevitably become strained.

My Thoughts in Conclusion

The word “why” is still very difficult to navigate between neurotypes, which is why this part of the guide isn’t as concrete in its explanation as I wanted it to be, but it may help give the neurodivergent people reading this some insight into why the word “why” can get such a volatile reaction.

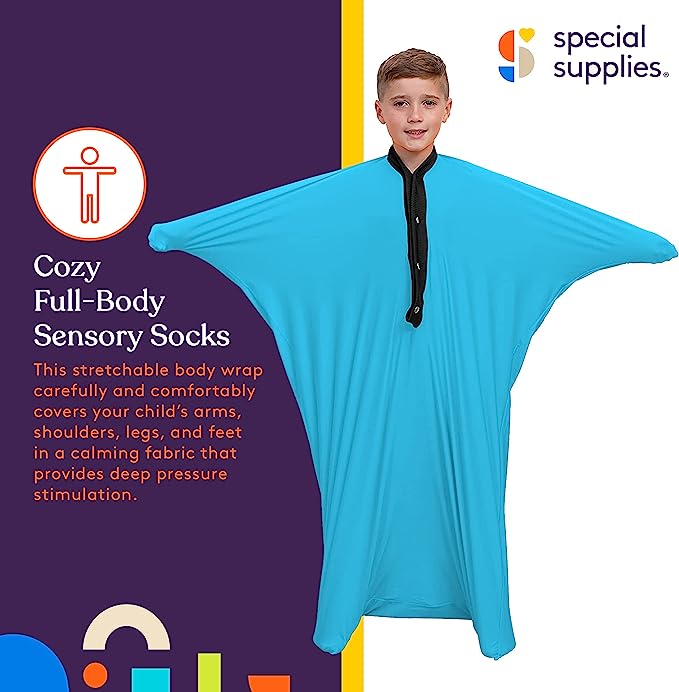

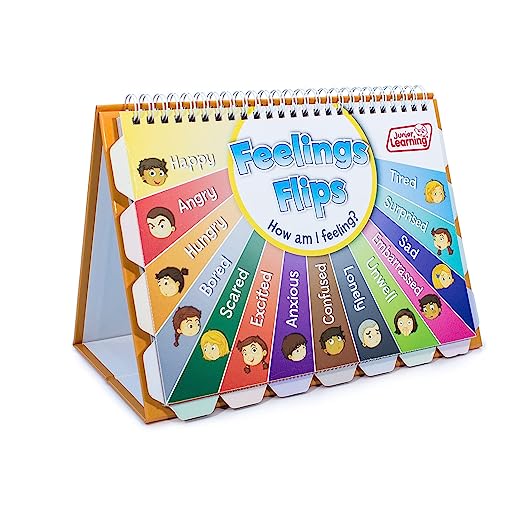

Books for Better Understanding the Autistic Brain

(Whether you’re an autistic person who is newly diagnosed, or you have a loved one on the spectrum, the books below can help you better understand the autistic brain.)

Want downloadable, PDF-format copies of these blog posts to print and use with your loved ones or small class? Click here to become a Patreon supporter!

I think this scene with the autistic secretary at the doctors office (doctor being aware of her ND), finding herself in distress, is completely unlikely to ever happen in the first place.

This doctor would be completely incompetent for his/her profession, since he/she would have been taught about ASD related problems during medical school and would never have hired her for this position, which would require insight in peoples voice over the phone and empathy when people are trying to give some brief description as to why they wish to make an appointment.

a secretary needs to ask followup questions [and assess the tone of voice in the answer] in order to assess the medical situation being explained.

Simple occasional unexpected tasks may occur.

As NDs tend to fail to accomplish such actions, they would be put in situations that would cause them lots of anxiety. This would certainly not serve any new patient.

so the scene seems very hypothetical.

It seems to serve the purpose of setting NDs as a poor victim of clueless NTs,

I think it underestimates the knowledge of any doctor.

Doctors, being people, also make mistakes, despite long education.

All of my scenes are hypothetical, Frank. They serve to illustrate a point by giving an example. They’re not meant to be taken literally. I know, I know, we take things literally, but these are just scenarios, like illustrations in a book.

The assertation that doctors learn about ASD in medical school isn’t helpful, especially regarding autism in girls and women, which presents very differently. And so very many physicians and other providers are cruelly clueless to this fact.

And some of us do well in patient care because we are sensitive to the needs of others and ask appropriate questions. We’re not emotionless robots.

And I have been in a situation where I was given additional responsibility outside the scope of my job, and it didn’t go over well when I asked “why?”

In my experience, the more competence the autistic person shows, the more that gets dumped on them because autistic people are nonconfrontational and are so eager to please that we say yes until we finally break.

When we’ve exceeded our limit and need to know why we’re being asked to do even more, whether it’s outside our capabilities or not, we pay dearly for it.