Iris Warchall, Autistic Physical Therapist, Discusses Common Health Issues Autistic People Face

Recently, I was asked to do a guest spot on a podcast called Autism Stories hosted by Doug Blecher. To prepare, I listened to a few of his previous shows, and I came across his interview with Iris Warchall. I was so fascinated by what she had to say about the physical differences and common health issues autistic people face, that I got in touch and asked her if she would do an interview for my blog, as well. I’m so grateful she agreed!

In this interview, I ask Iris about what it means to her to be a neurodiversity-affirming therapist, how a specific function of the autistic brain affects our difficulty with processing change, the differences in autistic physiology as opposed to neurotypical physiology, and what healthcare providers need to know in order to better serve their neurodivergent patients.

Let’s get into it!

Jaime A. Heidel, The Articulate Autistic:

You’re a neurodiversity-affirming physical therapist. Can you tell me more about that and how you came to use this awesome identity?

Iris Warchall, Autistic Physical Therapist:

“I’ll explain the order in which these various aspects of my identity, and my knowledge base, came to be.

First, I was a physical therapist, and an undiagnosed autistic person who had all the typical life experiences of an autistic adult who had no idea that they were autistic.

I wound up developing specialties in helping people with chronic pain and pelvic health conditions. Then, the fact that I was working with those populations wound up leading me to see a sizeable number of patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) and other hypermobility spectrum conditions. People with EDS are more likely to experience chronic pain and are also more likely to deal with certain bowel and bladder issues that we commonly see in pelvic health PT.

Meanwhile, I was parenting an autistic child, and largely because this child was female, she was undiagnosed until she was five years old. Throughout her infancy and toddlerhood, I noticed subtle but undeniable neurologic motor developmental differences, with which I was working to support her.

Prior to my daughter’s autism diagnosis, the pediatric healthcare professionals I had consulted with acknowledged that she did indeed have some neurologic movement differences, but that they weren’t significant enough to qualify her for any specific diagnosis.

I began thinking about how there were probably a whole lot of adults out there in the world who had undiagnosed motor developmental differences and began to notice subtle signs of what seemed like atypical motor development in many of my patients. I wondered how many of my patients had been similar to my daughter when they were young.

When my child finally received an autism diagnosis, it opened up the doors for me to find so much information that I never would have encountered otherwise. I learned a huge amount from the autistic self-advocacy community about how to support my child, and I recognized that I was also autistic, and I better learned how to support myself and ask for support from others.

I began to learn about the lived experiences of autistic adults who had movement differences, and I was able to become familiar with the literature about motor developmental differences in autistic people. There’s a large body of research about autistic movement differences, despite the fact that motor differences are only tangentially mentioned in the DSM-V diagnostic criteria for autism.

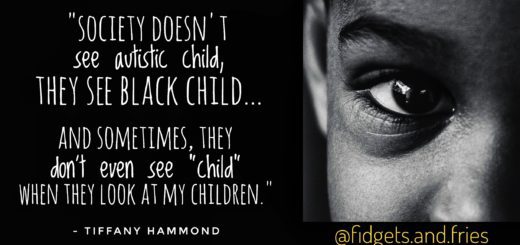

I learned that autistic motor developmental differences wind up affecting people’s communication, facial expressions, and body language, which then affects how autistic people are perceived by society.

I learned about the increased frequency of co-occurrence of autism and other types of neurodivergence in folks with EDS. I learned about the potential ways sensorimotor differences can affect posture and gait and coordination. I learned about how interoception differences can affect bowel and bladder function, and the ability to sense pain and other symptoms.

I learned about how unmet sensory needs and the complex trauma of being neurodivergent in our society can affect the body’s autonomic nervous system, which manages stress responses and all of our automatic body functions like digestion and breathing. As a physical therapist, I already knew autonomic function was a hugely important factor in someone’s outcomes with chronic pain and a variety of other health conditions.

I’ve made a lot of changes to the way I help my patients in light of all these considerations. I realized that despite the fact that autism is actually fairly common, these important aspects of how to support autistic adults were not covered at any point in any of my training or in my continuing education!

Now I’m on a mission to educate the physical therapy community, and the healthcare community more broadly, about how to provide better care for autistic adults.”

Jaime:

It’s pretty well known that autistic people struggle with change, but the reason is not always understood. You have written about how the basal ganglia of the brain affects this process in autistic people. Can you elaborate on that?

Iris:

“The basal ganglia are a group of neurons deep in the center of the brain that have connections with many other brain regions, including the areas that control thoughts, executive functioning, sensory processing, movement, and emotions. The basal ganglia help tell these other brain regions when to start doing what they do and when to stop doing what they do, and help tell the other brain regions at what intensity or amplitude they should be doing their functions.

You can think of the basal ganglia like a light switch with a dimmer function for other areas of the brain.

Neuroscience researchers have found that autistic people have differences in connectivity between the basal ganglia and other areas of the brain, as compared to allistic (non-autistic) people, and that this might potentially account for the broad range of traits that we call autism.

Essentially, if you’re autistic, it’s likely that you have more connectivity between your basal ganglia and some areas of your brain than most people do, and less connectivity between your basal ganglia and other areas of your brain than most people do.

This means that your brain would be able to start doing certain functions very readily, but other functions would be difficult to start. It also would mean that when your brain is performing a certain function, it may do so with more or less intensity than most people.

I think this way of conceptualizing autism really matches up with the wide range of experiences autistic people have. Each individual autistic person has their own pattern of which brain functions have more or less ease of starting or stopping, and which functions tend to be performed more or less intensely.

Our brains can experience any given sensory input with more or less intensity than the average person. We can have difficulty initiating some movement patterns (for example, motor functions related to coordination), and at the same time tend to initiate other movement patterns much more than most people do, sometimes to the point that we can have involuntary movements like tics that can limit function.

Ok, so now to specifically answer your question about transitioning between activities! It’s a common autistic experience to tend to be able to easily start focusing with great intensity on some trains of thought, and then have difficulty transitioning away from those trains of thought to shift attention to other activities.

If we think about this in terms of potential differences in basal ganglia connectivity, then the reason for not transitioning as quickly between activities could be explained by your individual wiring with the metaphorical “light switch with dimmer function” resulting in it being easy to maintain intense hyperfocus on a certain task once you get started. Your personal dimmer doesn’t dim down the intensity of your attention like it does for neurotypical folks. Then, because you have that strong connectivity with the part of the light switch that keeps signaling your attention to stay “turned on” at a high intensity, it’s hard to stop.

Other conditions with differences in basal ganglia function can result in atypical starting, stopping, and scaling of movements, sensory input, and/or thoughts. These include Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, other dyskinesias, tics, and dystonias, and are referred to as “movement disorders” by neurologists. Researchers at various points have questioned whether it might be appropriate to consider autism under the umbrella of movement disorders, or whether movement disorders are a major characteristic of autism.

As a physical therapist who has worked extensively with patients with Parkinson’s and other movement disorders, I believe that the evidence indicating a link between basal ganglia function and autistic traits needs to be discussed more seriously by the medical community. My lived experience, and my observations and understanding of other autistic people’s experiences, seem to match up with the hypothesis of autism being a difference in basal ganglia function.

Right now, autism is classified as a “behavioral disorder” or a “disorder of social behavior,” and because doctors think that way about autism, the most common support offered for autistic kids is ABA, which is essentially operant conditioning to try to extinguish autistic traits.”

“To me, referring an autistic child for ABA is like telling a person with a dystonia (dystonias are conditions resulting in involuntary movements) that the only available support is to earn a star on a star chart, and that they will lose a star each time they have an involuntary movement.

It’s like telling a person with Parkinson’s who has a tremor that the appropriate support for their tremor is that they will get an admonishment from their medical provider each time their hand starts shaking. It just doesn’t make any sense from a neurobiological perspective, and being subjected to an operant conditioning scheme that doesn’t make sense tends to be traumatic.” – Iris Warchall

Jaime:

You’ve worked with hypermobile neurodivergent people. Can you talk more about how autistic physiology is different from that of the neurotypical people you’ve worked with? What are the most common ailments you’ve seen in your autistic clients?

Iris:

“Well, no two autistic people are the same, both in terms of their neurology and in terms of what other conditions they as individuals might be more prone to developing.

However, there are a wide variety of other health conditions that autistic people are generally more likely to experience than allistic folks.

Autistic people have higher incidences of many of the conditions I help people with as a physical therapist: chronic pain, hypermobility spectrum conditions, pelvic health conditions that affect bowel and bladder and sexual function, and dysautonomias.

All autistic people have motor developmental differences of one kind or another. If you have movement differences that are significant enough to cause functional problems, you’re going to need a physical therapist to pick up on these and develop a plan of care that is tailored to your individual neurology. And if you are hypermobile, your physical therapist is going to need to specifically modify your plan of care to be teaching specific ways of using exercise and other strategies like bracing/taping/ergonomic supports to reduce the chance of injury from over-stretching your tissues.

**Trigger Warning – Mention of Suicidal Ideation**

All healthcare providers should be aware of the need to screen and manage or refer out as needed for the following other health conditions we know are more likely in the autistic population: autoimmune conditions and allergies, gastrointestinal issues, anxiety, depression, suicidality, and burnout.”

Jaime:

In your opinion, what are some of the common barriers autistic people face in accessing effective healthcare?

Iris:

“There was a study published earlier this year discussing barriers autistic people commonly have in accessing healthcare. The most common barriers the authors of the study identified were “deciding if symptoms warrant a GP visit (72%), difficulty making appointments by telephone (62%), not feeling understood (56%), difficulty communicating with their doctor (53%) and the waiting room environment (51%).”

Another 2019 study found “patient-provider communication, sensory sensitivities, and executive functioning/planning issues” were barriers to healthcare for autistic people.

To me, these findings pretty much summarize the major issues, but it’s important for clinicians to understand how these barriers play off of each other in order to effectively mitigate them.

Prior negative experiences with “not being understood” by, or “difficulty communicating with” healthcare providers due to a lack of provider understanding of autistic communication styles (including facial expressiveness and body language) can be a major driver behind the mental calculus an autistic person will be going through when “deciding if symptoms warrant a GP visit.” If you’ve previously had your concerns misunderstood or inappropriately dismissed, you might be hesitant to go to the doctor and have that happen again.”

“The waiting room environment,” and more generally the sensory environment in the entire facility, can make communication and executive functioning more challenging if your brain is starting to become dysregulated due to bothersome sensory input.”

Jaime:

Is there anything else you would like readers to know about you? Hobbies? Pets? Children? Favorite shows?

Iris:

“Well, if you couldn’t tell yet, I’m a neuroscience geek.

I love to run for exercise, but I have to work at taking care of my body to allow myself to do so without pain because some of my autistic movement differences make me more injury-prone.

In the middle of the pandemic, I went through a phase of teaching myself how to draw and paint and hyperfocused on those activities until I ran out of space to store paintings in my house.

I’m the parent to an awesome kid, and lucky to have an equally awesome and supportive spouse. We spend a lot of time in my household repeating funny phrases from books, movies, and songs. I recently adopted two fluffy brown tabby cats, Shirley and Wiley, who also give me great joy!

Thank you so much for the opportunity to discuss these topics. I’m really hopeful that as more and more voices of neurodivergent healthcare professionals and researchers are heard, the standard of care for autistic people provided by the medical community will be able to improve dramatically.”

Connect With Iris!

I want to thank Iris again for generously offering this comprehensive and informational interview. If you want to connect with her on social media, check her out on Instagram here!

Click on the link below for a list of books written by autistic people that can help you better understand your autistic loved one.